The idea of a transcontinental highway in the West, spanning from Mexico to Canada, has been kicking around for decades. The possibility of this “CANAMEX” route, bookended by two international trade ports, has stirred high hopes for greatly expanding trade opportunities, industrial development, and new jobs for people and communities throughout the West.

In 2012, Congress approved a transportation omnibus bill (MAP-21) that designated what could become the first segment of this route as a future Interstate 11 (I-11). Phoenix and Las Vegas are the two biggest cities in the United States not connected by an interstate. Interstate 11 would provide this connection, as well as a link to Mexico and to points north of Las Vegas.

MAP-21 provided funding for the planning and study of possible corridors routes for I-11. What it didn’t provide was funding for the highway itself.

“The days of earmarks for federally funded interstates have been gone for a long time,” says Ian Dowdy, director of our Sun Corridor program, based in Phoenix. “It’s likely that much of the money for this project will have to come from state taxes and maybe tolls. The only way for the I-11 to move forward is if the public sees it as a project that is going to change their lives and that they can’t live without. The same old highway model won’t do that, and would be something the Sonoran Institute would be unlikely to support. This has to be a project that will completely change our future as a community and provide opportunities to harness and protect our region’s greatest assets—our proximity to Mexico and role as a key trade corridor, our renewable energy potential, our highly educated and skilled labor force, and our unique natural resources.”

Designed By the Future

So, who better to design the interstate of the future than the people who will be using it in the future?

In 2014, the Sonoran Institute participated in a unique and exciting project involving three universities that the future I-11 could connect: the University of Nevada-Las Vegas, Arizona State University in Tempe, and the University of Arizona in Tucson. With funding from the Walton Sustainable Solutions Initiative and UA’s Renewable Energy Network, the three universities had embarked on a multidisciplinary “design studio,” where students in landscape architecture, urban planning, architecture, and other disciplines collaborated to envision designs for different segments of I-11.

Linda Samuels, then director of the Sustainable City Project at U of A and currently associate professor of Urban Design in the Graduate School of Architecture and Urban Design at Washington University, was one of the leaders of the project. “Our challenge to the students was to think about leveraging the massive investment that will go into the I-11 to do something that is socially and environmentally productive rather than just moving cars. We asked, ‘What would that look like, and how can we make the case that it is a better option?’”

One of their first moves was to involve the Sonoran Institute. Ian Dowdy had done considerable research on sustainability metrics to determine the route alternatives that would produce a less destructive, more productive roadway. He was able to share maps and critical data on wildlife habitat, population demographics, and renewable energy opportunities. His presentation at an opening event with all the student and faculty participants and Arizona Department of Transportation (ADOT) not only set the context of the project but also its ethos.

“What we learned, first and foremost, was the Sonoran Institute’s collaborative posture,” says Ken McCown, who was then director of UNLV’s Downtown Design Center and now head of the Landscape Architecture Department and adjunct professor at the Fay Jones School of Architecture at the University of Arkansas. “For the faculty and students coming into the project, we were familiar with this idea that pervades our culture that development and nature are at odds with one another. The Sonoran Institute presented to us that there are diverse stakeholders involved, including energy industry groups, the Arizona Department of Transportation, environmentalists. We were able to see that these groups with different interests were all talking to one another to achieve common goals. Just to hear and see that right from the start of the project set a tone for us that there is a positive vision moving forward for the future. It gave us energy. It gave us a belief that we could make a difference.”

A Highway Bridge Builder

Highways are notoriously disastrous for the environment, scarring landscapes, disturbing plants and wildlife, and spreading sprawl. For all of these reasons, conservation organizations are typically steadfast opponents of highway construction.

But the Sonoran Institute is not a typical conservation organization.

“Balancing economic growth with protecting our natural resources is a challenge, but we don’t believe it has to be an either-or choice,” says Dowdy. “If the I-11 is thoughtfully designed, we believe it has the potential to help usher in the ‘next generation economy’ to the Intermountain West—in a way that minimizes the impact on our fragile desert landscape.”

The “next generation economy” is one that relies less on construction and population growth and more on sustainable development, such as renewable energy production, as the region’s economic engine. Arizona’s solar and wind energy potential are sky high, and the largest market for this energy happens to be next door in California. However, lack of transmission capacity to deliver this energy to market continues to be a major stumbling block.

“We believe the I-11 corridor could be a catalyst for realizing Arizona’s renewable energy potential and empowering an economy that will support high-quality jobs in a sustainable way,” Dowdy says. The key, the Sonoran Institute believes, is for the I-11 to be designed as a “multimodal” smart corridor that, beyond just the highway, also encompasses energy transmission, passenger and freight rail, and data transmission. Historically, these various infrastructure elements have been built in separate but parallel rights-of-way, spreading and compounding the harmful effects on the environment. Integrating all of elements into one smart corridor reduces the environmental footprint.

A Champion for an Alternative Vision

Over the course of the design studio, Dowdy attended design reviews, met with students on a regular basis, went on tours, and even took two students on an aerial flight so they could photograph the site for their class to use. He connected the faculty and students with stakeholders and got the students up to speed on the context, history, landscape, and environmental risks involved with the I-11 project.

“Successful projects need project champions,” Linda Samuels says. “The Sonoran Institute has been a persistent shepherd of an I-11 alternative. Our students were very sensitive to issues of wildlife, habitat preservation, historical and cultural preservation, and water capture and conservation. Ian showed them that there are professionals out in this world who are fighting for people and the environment as part of development. These are viable options – you can go out in the world and do this for your job.”

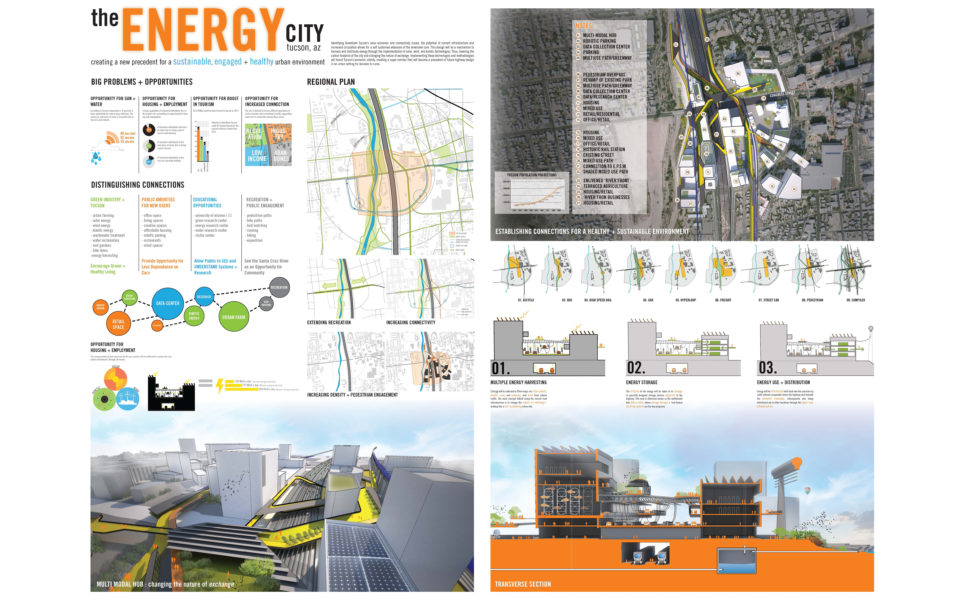

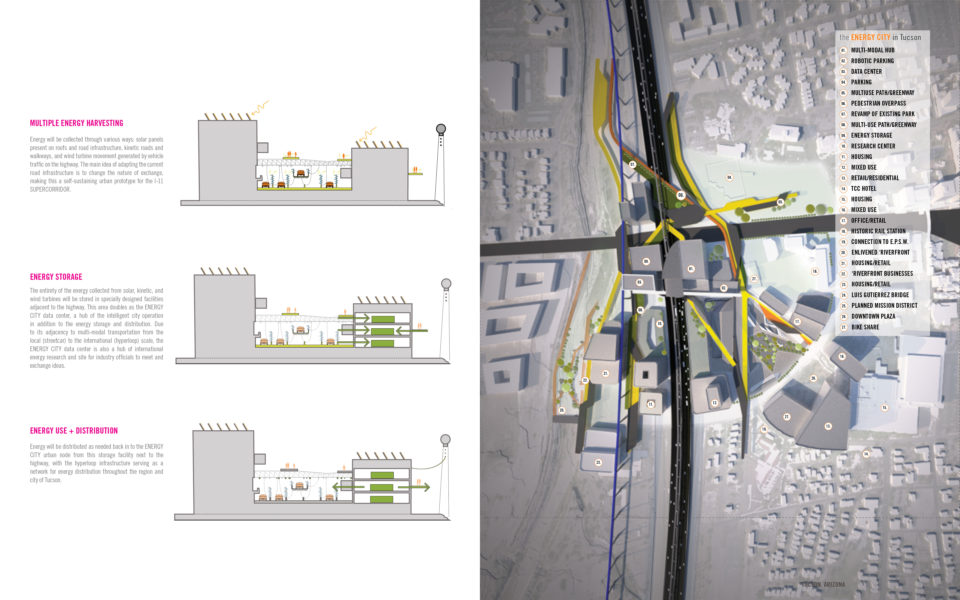

Extending through a semester and a summer term with a smaller, focused team, the design studio produced a document more than 230 pages long that sets forth a vision of the I-11 which does much more than move cars. The study considers how communities could make full use of the new infrastructure, such as turning an intersection in Tucson into an “Energy City,” where new retail, office, and hotel space is developed around a transportation/energy/water-recycling hub that includes high-speed rail, driverless cars, car sharing, and solar-charged car technology, walking and biking paths, and green space.

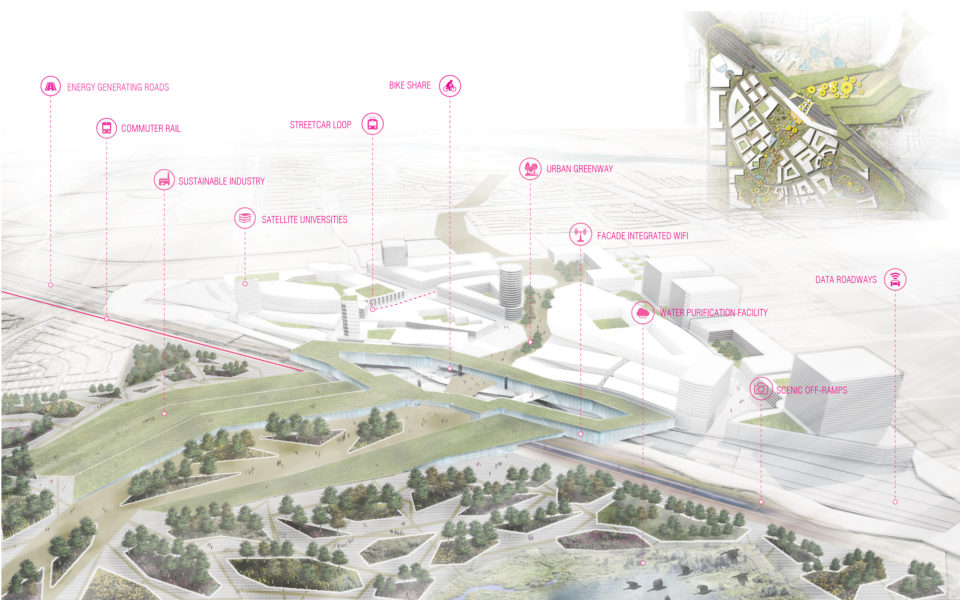

For the Marana stretch, the study explored how freight and passenger rail, highway, and walking and biking infrastructure could be integrated into a new green corridor that capitalizes on and enhances the area’s natural water resources. This transportation hub would attract new high tech industry and advanced education to Marana. This growth would be concentrated around the “green arm” running through the city, providing an area for new, sustainable economic activity while protecting the surrounding environment.

UNLV students identified renewable energy and ecotourism as economic development opportunities for the environmentally sensitive stretch from the northwest edge of Phoenix to Las Vegas. Their analysis concluded that the driverless cars of the future will allow for a much denser concentration of traffic, where the cars can safely maneuver much like pieces in a Tetris game.

“These efficiencies would make it unnecessary to increase the width of the roadway, which is crucial to preserving habitat and other sensitive resources,” says Ken McCown. “Keeping the road narrower also allows for wildlife habitat overpasses to be built across the road so wildlife can safely cross, and so passengers—who no longer have to worry about keeping their eyes on the road—can become ecological tourists. They can see and learn about the area’s plants and animals as they pass through.” Unused space in the present corridor right-of-way could also be used for high-speed rail, energy transmission, and wind and solar energy generation as the Interstate 11 develops.

Changing Attitudes and Perspectives

The future is fast approaching. “It’s amazing how much has changed in just the two years since we began this project,” Samuels says. “Autonomous vehicles, solar-charged electric vehicles, car share – all of that is common talk now. Autonomous vehicles are coming online at a rapid pace, and high-speed rail is getting built in California. Our proposals look less and less outlandish and more and more possible.”

One of the biggest successes of the project, Samuels says, was getting ongoing support from the Arizona Department of Transportation, who partnered with the studio from the beginning. “We feel that we have been instrumental in getting ADOT to think a little differently about the highway,” she says. “When I would present this to stakeholders, some would say, ‘This isn’t possible. This is futuristic. ADOT would never do this.’ ADOT representatives would actually answer, ‘This is not futuristic at all. We’re talking about a $10-13 billion investment, and the risk of being obsolete is too great if we’re not thinking two to three generations ahead.’”

In addition to being willing to think beyond the traditional highway model, ADOT has also adopted a more sustainability-focused way of assessing the environmental impact of the future corridor. “It includes more metrics around environmental protection and social equity—not what they typically measure or focus on when they do a highway project,” Samuels says. If this new kind of environmental impact statement becomes the filter through which all other infrastructure projects go, it could have a dramatic and long-lasting effect. “To me, this feels like the start of something.”

“The Sonoran Institute has been a persistent shepherd of an I-11 alternative. Our students were very sensitive to issues of wildlife, habitat preservation, historical and cultural preservation, and water capture and conservation. Ian showed them that there are professionals out in this world who are fighting for people and the environment as part of development. These are viable options – you can go out in the world and do this for your job.”

– Linda Samuels, director of the Sustainable City Project at the University of Arizona.

Engaging the Next Generation

Through the response he saw in his students, McCown also predicts the design studio will likely yield wide-ranging and enduring implications for the future of the West. “When we’re talking about reaching out to the youth, they need stepping stones, they need a path to be able to see the reality of what this work is like, and they need real people that they can hold up as role models,” he says. “One of the hardest things I have to do with my students is to advocate for them going into the nonprofit sector. It’s eye-opening for them to see that Ian and the Sonoran Institute get a seat at the table with very important players. It helps students understand that the real value to what we do as designers is not so much to make money but to know we’re having an impact.”

If it hadn’t been for the Sonoran Institute’s involvement in the project, McCown says, his students would never have understood the significance of the big horned sheep, and why patches of habitat need to be connected to keep their gene pool diverse. They never would have understood renewable energy development land, and how policy affects land use.

“And, now, instead of looking to move to New York, Chicago, or Los Angeles after graduation,” he says, “we had more students stay in Las Vegas, because they now feel connected to the place and its surroundings, and are invested in creating a more sustainable future. They have seen futures they did not think were possible and can see themselves partnering to shape new visions in their community and ecological context.”

Images of team renderings provided by Linda Samuels.

Teams:

Marana Section | [RE]FORMATION

Stratton Andrews, BArch, University of Arizona

Daniel Aros, MLA, University of Arizona

Will Greenway, MSP, University of Arizona

Alex Hines, MSP, University of Arizona

Yang Yang, MLA, University of Arizona

South Tucson Section | THE ENERGY CITY

Steven Giang, MSP, University of Arizona

Sally Harris, MSP and MBA, University of Arizona

Kendra Hyson, MLA, University of Arizona

Katie Laughlin, MLA,University of Arizona

Bernardo Teran, BArch, University of Arizona

Wildlife Crossing in Wikieup, AZ

Amanda Gann

Emylanie Carnate