The sun is just rising through their school bus windows, but these fourth graders aren’t going to school. Instead, they are doing something some of them have never done before; they’re taking a trip outside their city of Mexicali, the capital city of the Mexican state of Baja California. The bus windows are clouded by the ever-present desert dust, industrial smog, and smoke from burning trash that chokes their air. They make slow progress through traffic that takes them past block after block of pavement and concrete but by very few parks or other greenery. It is hot and exceedingly dry. The rare waterbodies they see are agricultural drains lined with dirty, standing water and debris. As they leave the city limits, space opens up to agriculture fields but no real natural areas. Many of the open areas along the way that are not being cultivated with food are growing mounds of old tires, garbage, and other illegally dumped trash. Eventually, the bus begins to follow a canal that runs parallel to a mostly dry riverbed. The canal is transporting water diverted from the Colorado River. The mostly dry riverbed is the Colorado River. But the kids don’t know that—yet.

Finally, about an hour outside the heat and hardscape, the bus comes to a stop. The door opens, and—like magic—the children step straight into a thick, shady forest. With animals. And bugs. And water.

“They’re actually a little scared,” says Gabriela González-Olimón, environmental education coordinator for our Colorado River Delta program. “They feel like they’re in a jungle. Many have never been in a place like this. Even some of the teachers can’t believe this really exists near Mexicali.”

The students have arrived at our Laguna Grande Restoration Area in the Mexicali Valley. Sonoran Institute-led efforts beginning in 2007 to plant and nurture native cottonwood, mesquite, and willow trees have transformed this area into the largest (nearly five river miles) and most-dense stand of native riparian habitat along the Colorado River in Mexico. It is one of the few green open spaces in the region, and one of the only places to see flowing water in the Mexican stretch of the Colorado River.

Bringing students to the site is one component of our expanding focus on educating and engaging young people in environmental conservation. In addition to programs in the Colorado River Delta, we also sponsor educational programs about the Santa Cruz River in Arizona.

Awakening a Deep Cultural Memory

“Our belief is you can’t care about what you don’t know,” says González-Olimón. “So many children in Mexicali don’t have the opportunity to get out of the city and experience nature. Most of them don’t know where their water comes from. Our program allows them to see first-hand a river they thought was long gone. They can see for themselves all the life that water in the river makes possible. For our work to have long-term success, we have to connect the new generation to the river, as we will need them to be champions for this work.”

Guides take groups ranging from kindergarten through university students into the forest. For nearly three hours, they follow bobcat and coyote tracks, identify bugs and plants, spot migratory birds, and see beavers and other wildlife they would otherwise never encounter. Since 2015, over 4,000 people have visited the site, including more than 30 school groups (about 1,200 students) in 2016, during the first year of our fieldtrip program. Numbers are expected to keep increasing as word of the program and its value spreads. “Living the experience is the most effective way for my students to learn about ecosystem problems and, specifically, the river,” says Edna, a high school teacher visiting with her class from Mexicali. “The Sonoran Institute’s programs also help me get trained and updated in subjects related to the environment we live in.”

Outside of the school programs, our Family Saturday programs provide an opportunity for people of all ages to visit the restoration site for a free guided tour, birdwatching, kayaking, and a chance to see the river that most thought had disappeared with their grandparents’ generation.

“The reactions are incredible,” says Dzoara Rubio, our environmental education assistant. “For the older people, it’s mostly tears when they see the river and the forest—things they’ve heard stories about from their parents and grandparents and are now able to experience with their own families. Seeing the river alive again generates very powerful emotions in the people of Mexicali. It’s waking up memories that connect them with past generations, with their heritage. They instantly care about the river because it’s part of them. So, in addition to our successful ecological restoration, this cultural identity is another dimension of what the Sonoran Institute is rescuing in the Delta.”

Tapping further into the Delta’s environmental consciousness, we plan to expand our education programs to include more communities, especially those whose close ties to the river reach back centuries, such as the Mexicali Valley population and the indigenous Cucapah community. Our goal is to eventually include all of our restoration sites in the program and to continue installing interpretive centers, signage, and bird-watching towers to reinforce visitors’ educational experience.

Discovering the Living Santa Cruz River

Across the border and a couple hundred miles as the crow flies, our restoration activities for a tributary of the Colorado River, the Santa Cruz River, provide opportunities for students in Arizona to learn about the environmental treasure in their own backyard.

Like the Colorado, the Santa Cruz is a binational river and in fact has the distinction of being the only river to cross the U.S./Mexico border twice. Originating in Arizona’s San Rafael Valley, it dips into Sonora, Mexico, and then makes a horseshoe turn before crossing back into Arizona around Ambos Nogales. From there it flows north through Tucson and eventually joins the Gila River, which flows into the Colorado. A critical water source in the desert, the Santa Cruz has been drawing people to its banks for over 12,000 years, from the native Tohono O’odham people to Spanish settlers and missionaries and eventually American settlers.

One of the legacies of the mixture of cultures drawn together by the river is the rich food heritage the region enjoys today. In 2016, Tucson became the first U.S. city to earn the title “UNESCO World City of Gastronomy,” thanks largely to its diverse food traditions and ability to claim the longest agricultural history on the continent—all made possible by what in many ways has become a forgotten river.

The flip side of the importance of the Santa Cruz has been its exploitation. The river never flowed year-round from end-to-end, but heavy irrigation use and groundwater pumping over the last century dried up the long stretches that did regularly flow. The Santa Cruz is now dependent on effluent—highly treated wastewater—for much of its flow. Until upgrades to the Nogales International Wastewater Treatment Plant in Rio Rico, Arizona (2009), and to two treatment plants owned by Pima County in the Tucson area (2014), poor water quality had rendered the river virtually fishless and miles of riverbank barren.

“We have been focused on restoring the health of the Santa Cruz River and its watershed since the Sonoran Institute’s founding in 1990,” says Claire Zugmeyer, Sonoran Institute’s ecologist. “In 2009, we embarked on an effort to understand the health of the river and how it was changing so that we and the many other organizations doing conservation work on the river could better direct our stewardship efforts. That is when we launched the Living River initiative. Our annual Living River reports documenting conditions on the Santa Cruz have been an important part of this effort ever since.”

The first series of Living River reports focused on a 20-mile stretch of the river from Rio Rico to Amado in Santa Cruz County, Arizona—confusingly referred to as the “Upper Santa Cruz.” Even though it is the southern stretch of the river, the “Upper” refers to its higher elevation. Beginning in 2012, we started documenting conditions on what the Sonoran Institute refers to as the “Lower” Santa Cruz River (the northern, lower-altitude stretch with effluent flows) as well, as part of a joint initiative with Pima County. The first Living River report for the Lower Santa Cruz documented baseline conditions in a 23-mile stretch northwest of Tucson before Pima County invested $600 million to upgrade its wastewater treatment facilities. Since then, we’ve been tracking the changes and improvements in the Santa Cruz River with respect to its native fish, wildlife, and the overall ability of the public to enjoy the river.

A “Forgotten” River Reemerges

Our Living River reports provide the backbone of our educational outreach activities for the Santa Cruz. The Living River of Words is a program for students age 5-19 that explores students’ relationships to the river through both art and science. Pima County’s Living River Academy, a two-day seminar for teachers in the area, guides teachers in how to use the Living River report in their classroom. Both aim to build awareness and appreciation of the importance of the river environment.

“Thanks to the effluent from Pima County’s reclamation facilities, water flows in much of the Lower Santa Cruz River year-round, but a lot of people aren’t aware of it,” says Zugmeyer, who coordinates the Living River reports. “The river has been hidden behind commercial neighborhoods and has only recently become more accessible through the LOOP recreational trail and other parks that have been built in the Tucson area as the river conditions have improved. Still, so many students—and parents—are unaware there is a river there, why it is important, or where their water comes from. We’re working to change this.”

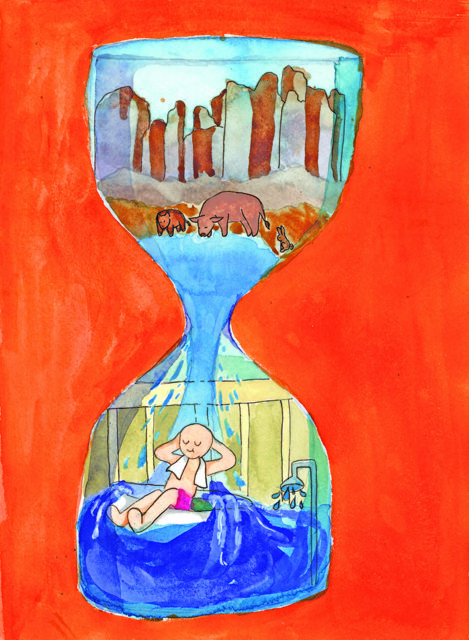

Through the Living River of Words, students learn about the river on many levels: by visiting it, creating artwork about it, and using Living River reports to understand its ecology. Sonoran Institute provides funding for the field visit transportation and for a visiting artist to work with students on creating poetry and visual artwork related to the river that they can submit to the program’s annual art contest. Winning entries form a traveling exhibit shown in public libraries and art galleries throughout Pima County. Some of the work is also published in the Living River report.

Caroline Pechuzal, a high school environmental science teacher at Flowing Wells High School in Tucson, has participated in both Living River Academy and the Living River of Words. She uses the Living River report to stay up to date on what she’s teaching in her classes, and takes full advantage of the Living River of Words to make her classes meaningful.

“The single most effective way to engage students and get them more interested in the environment is to get them INTO the environment,” she says. “They need that tactile experience interacting with the environment to really get excited and interested. Public schools have limited funding to provide these experiences—and a lot of families can’t afford it, either. That’s why it is so valuable for organizations like the Sonoran Institute to support the schools through funded programs like these.”

“Something like 80 percent of the kids who participate in Living River of Words have never seen a flowing river before,” says Evan Canfield, of Pima County’s Regional Flood Control District. “The Living River of Words has probably been the best public outreach about the river on the Lower Santa Cruz that we have. It has heightened awareness about the river and moved discussion about it into the classroom. From there, it spreads to the parents. As a parent, there are few more effective ways of getting my attention than when my son comes home and asks, ‘Dad, did you know . . .?’”

Since 2015, over 2,000 students have made field visits to the river and 3,000 have submitted entries to the Living River of Words art contest (a field visit isn’t required for participation in the contest). Looking ahead, we plan to work with our partners to develop a teacher’s guide that will help expand the number of students exposed to the Living River curriculum.

Natural Wonder

One of the children getting out of the bus that day in the Colorado River Delta was a girl who immediately attached herself to Gaby González-Olimón. “Marianna was glued to my side for the entire two-hour walk, interested in everything, asking questions, talking over the other kids, unable to contain her excitement,” she says. “I love nature!” Marianna announced. At the end of the tour, their group and the other small groups of classmates reunited to have lunch, compare their scavenger hunt discoveries, and play some games to finish their day. Marianna was an enthusiastic participant.

“For me, she was a normal girl, very excited about everything, a normal 4th grader,” González-Olimón says. As the children played, the school principal approached González-Olimón, crying, and hugged her. “I don’t know what you did to Marianna!” the principal said in amazement. She explained that, at school, Marianna is considered a special education student. She doesn’t talk, have friends, or participate in class. Out in the woods, she was an entirely different person.

The sun had shifted in the sky when Marianna and her classmates returned to Mexicali, but otherwise their city was unaltered. The same could not be said for many of them. Two days later, González-Olimón heard again from the principal, who told her that Marianna’s astonished parents had called to ask what had happened to transform their daughter.

“We made a positive change,” González-Olimón smiles.