There are many Wests. We live on a sphere, it’s unavoidable. The curators of the University of Arizona Museum of Art’s The Myth and the Mirror: Artwork of the American West, Dustin Shores and Eric Wilson, explain that the West is both real and imagined, embodying the “fraught interconnections between exploration and colonization, national identity, and manifest destiny.” We asked whether the art in this exhibition would relate to Sonoran Institute’s mission to connect people and communities to the natural resources that nourish and sustain them. Would “our” vision for the West be one of the ones represented?

Back in college we both studied art history, and came by way of museum work into natural resource conservation. It’s not the most straightforward route, but like you, we have many interests. We are drawn to non-profit work and making a difference.

As native Tucsonans, we feel that the West is home. Our memories are sunbaked, we’re not afraid of snakes and our yards have always been covered in cactus. As art historians we like to think about the world using works of art to take the pulse of a culture at a specific time and place.

Elise: The works in this show run the gamut from placid landscapes, to red-blooded genre works, to no-holds-barred takedowns of colonialist bloodshed and the commoditization of national parks. Each one represents a perspective on the West that is colored by each artist’s story. As much as those perspectives loudly clash with each other within the four walls of the gallery, there is a common thread that immediately jumped out at me, as cliché as it sounds: the impressive beauty of the natural world.

The West has hosted waves of immigrants and their stories since the first people to reach the continent arrived close to 20,000 years ago. Since then, there have been colonizers, conquerors, missionaries, adventurers, fortune seekers, refugees, and countless others. I am here because my father’s family originally came to Tucson in the 1960s via the Air Force to escape racism and segregation back east. What awaited those folks was not always what they hoped for, but a sense of place took root that was hard to escape.

I think that irony is echoed in my favorite piece in this exhibition, Yasuo Kuniyoshi’s The Cowgirl. It first stuck out to me because it was almost the only work in the show with a woman whose face you could see. I was drawn to the glum but clearly capable female figure rendered in a palette that is both unnerving and cooling. The sky occupies more than half of the painting, echoing her pallid face and shadowy clothes. Behind her, dead grass languishes half-heartedly next to snow-capped red hills.

As soon as I saw that this work was painted by a Japanese American artist around 1941, I knew the dark implications that date would have for someone of his ancestry: internment camps, almost all of which were in the West. Although Kuniyoshi, who was living in New York, avoided the camps, he was repeatedly denied citizenship and categorized as an “enemy alien.” What was the West to him, then?

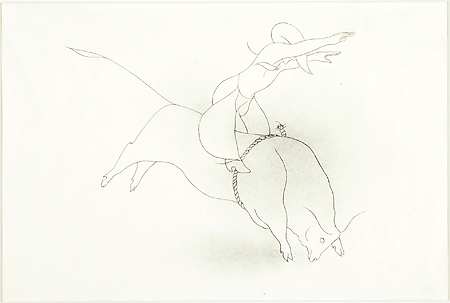

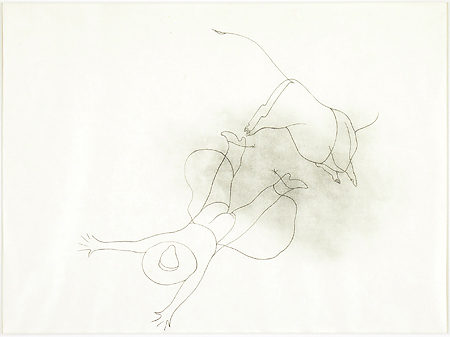

Corinne: Two deceivingly simple sketches were among my favorite pieces in this exhibition’s collection: Arthur Murphy’s lithographs, Bull Rider and Bull Rider #3, have this underhanded, clean style that like an open desert expanse seem unassuming until you really look. They are full of gesture and movement. The subject matter (cowboys) is iconic, something that has its place in our lexicon of the West and hopefully always will. But, these prints are not “cowboy art” in the glorifying sense. I wonder if the handful of people I know from ranching families, or the folks I see in trucks on open range when I go out camping would recognize themselves in these bull riders?

There is also a lot of humor here. The top image has a bull rider looking the part, holding on while the bull bucks him (her? are those pigtails?) up in a lurch—and in the second image we see (s)he has fallen face down. The artists’ graceful lines feel so much more recent than their 1930’s provenance. Murphy’s work is a distraction from the discomfort I feel with other pieces in the exhibition that touch on true despair, which perhaps they were for the artist too. They were commissioned, after all, through the Federal Art Project during the Great Depression.

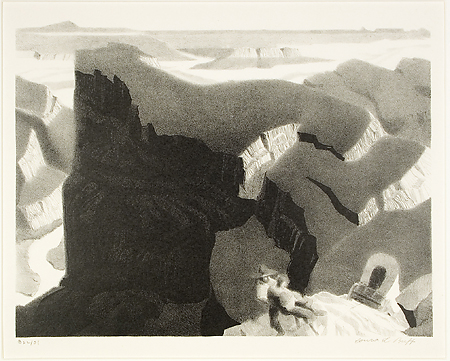

Elise: Still in my treasured “nameless dread” class of landscapes is Conrad Buff II’s American Pioneers. This modest lithograph lightly abstracts canyons and cliffs into planes of light and shadow, making the struggling pioneers towing their wagon uphill—a baffling feat for two men—seem like an afterthought. The skewed perspective of the cliff is exacerbated by the big plop of dark shadow that seems to pinch into a sinister claw, plucking the two men into the abyss just as they’re about to escape. Here, the sky is barely visible; there are no plants, and the s-curve of a winding riverbed squeezed into the lower left corner seems to be just another field of light, lifeless and dry.

Corinne: What gets me in this piece is the shadow. Whatever’s casting it can’t be seen in the image, but it must be huge and tall—an omen of misfortune for the men trying to pull their wagon. Shade and darkness is represented in our culture almost always as a negative. However, as a native to the desert, shade is something I seek out, desiring its coolness and a reprieve from the sun’s glare. If I have to wait outside on the street for anything—a taco, a friend, or a ride—I always, always look for shade. If there were ever a good place to have to haul a wagon the shade would probably be the best spot in the entire scene, but you can tell that this shade is just not the welcome kind. Is this because the artist was born a Swiss man, and lived in Wisconsin and California more than he ever did in the West? Is he yet another person claiming that the Western landscape is exciting, but your life here will be hard? Will there be a day when we conserve shade as the natural resource it is? Probably not, but the gently bending river below is exactly the kind of thing we work to protect from drought and unplanned growth.

Elise: A very nice parallel is created across the room with Merril Mahaffey’s View of Battleship Arizona, a big colorful canvas reminding us of the monumental backdrop for all our human drama in the West. It is simply a beautiful sight. In front of it is a mirror (placed by the curators) that visitors can use to position themselves in the landscape via reflection, reminding us that when we look at these works we obscure the original vision of the artist merely by using our seasoned eyes. We become an impermanent imprint that both obscures and becomes part of the pristine land. This is the liminal space where myth is created; part imagination, part unknowable and awe-inspiring natural wonder.

So how does this all relate to Sonoran Institute? We see a core value of ours woven throughout the exhibition: finding a common ground. In this case, that is literally The Ground. All the myriad voices in this show came together to reflect the myth of the West in a way that acknowledges the history of our region without shying away from the dark lessons learned. Sonoran Institute’s vision of the West is one where civil dialogue and collaboration are hallmarks of decision making, where people and wildlife live in harmony, and where clean water, air, and energy are assured. We believe that we must preserve the connection between people and the land. There would be no West as we know it without the iconic landscapes represented in these works.

At Sonoran Institute, we believe that to protect the land we all love, we must bring everyone to the table for collaborative solutions that go beyond today’s divisive climate. That is why art is such a useful tool in discussing our mission: it is a way to share perspectives and find common values on a supremely human level. It reminds us that conservation is more than just science, it needs to inspire people and remind them that this is something worth protecting.

Note: While this exhibition is no longer available, we highly suggest visiting UAMA’s excellent collection for more Western art.

Blog Post By: Elise Christmon, Development Coordinator, and Corinne Matesich, Marketing Communications Coordinator