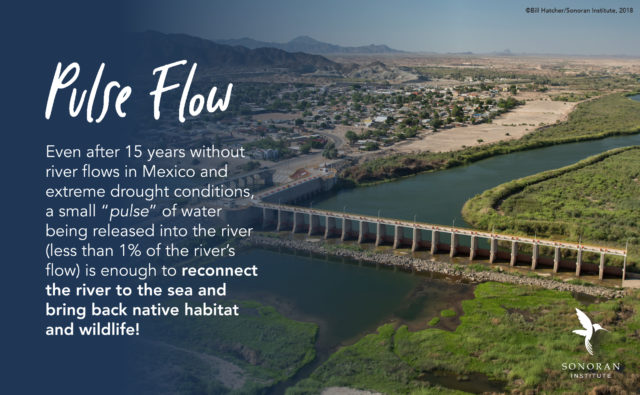

On Friday, the International Boundary Water Commission (IBWC) formally released an important report detailing the results and lessons learned from water deliveries to the Colorado River in Mexico as part of a binational agreement between the US and Mexico from 2012 through 2017. One of the greatest achievements of the work was the 2014 “pulse flow,” a release of water that reconnected the Colorado River to the sea. The people, plants and animals in the Colorado River Delta essentially had a massive party to celebrate the arrival of water.

I was there in 2014 when the pulse flow made the Colorado River (temporarily) whole again. The day that the gates of Morelos Dam opened and the river got to flow once again on its natural course into Mexico, I was super freaking busy. I was frantically finishing setting up a field experiment to evaluate how plants in the Delta would respond to the pulse flow (spoiler alert: they liked it a lot). So, although I missed the champagne celebration with our binational partners at the dam that first day, I basically lived in the field during the entire 8-week period of the flow release and afterwards, conducting research alongside an incredible multidisciplinary team of scientists from the US and Mexico. There was little sleep and lots of excitement, nightly calls with the Science Team to share updates on where the water had moved, flat tires, obstacles, team dynamics, and tireless commitment.

The amount of water that flowed into the river during the pulse flow was less than 1% of the river’s annual flow. But incredibly, even that small amount of water was enough to restore over 1,000 acres of native habitat, draw thousands of birds to the flowing water, and critically reestablish a relationship between local people living along the river and their natural environment. Less than 1% of the river’s total water not only revived plants, wildlife, and the human connection with the river, but it also revived hope and pride that two nations of people, boldly and against all odds, could collaborate to achieve diverse goals.

This report summarizes the high points of research conducted by a Science Team that go so much deeper than that one, exciting day. The report covers five years of dedicated research as well as results from smaller water deliveries. Together, 39 scientists from different institutions on both sides of the border conducted research to understand the many elements that make up the important ecosystems in the Delta.

This was a landmark effort because it was a first—the data we had about the Colorado River Delta at the time was incomplete. We had questions that we knew could be answered by focusing the science and monitoring on measurable indicators, and those answers would help determine the best ways to further manage and support this vulnerable and degraded system. Experts from both the US and Mexico each have unique expertise and viewpoints; studies were leveraged to build connections and support a common goal. There’s no way we would have gotten to this comprehensive understanding without that collaboration.

Some scientists looked at bird populations and diversity, like Osvel Hinojosa, previously at Pronatura Noroeste, others like Eliana Rodríguez and Jorge Ramírez at the Universidad de Baja California developed hydrological models and assessed groundwater, while Fátima Luna of Sonoran Institute conducted surveys with local community members to understand their perspective on the water releases and restoration. I co-managed the Science Team alongside Karl Flessa of the University of Arizona and Eloise Kendy of the Nature Conservancy, coordinating the research and reporting during the term of the binational agreement, and I worked with Pat Shafroth of US Geological Survey and Martha Gomez of University of Arizona on vegetation monitoring and analysis. Others on the Sonoran Institute team conducted monitoring in the estuary region, compiled results from our restoration sites, and participated on the Environmental Working Group.

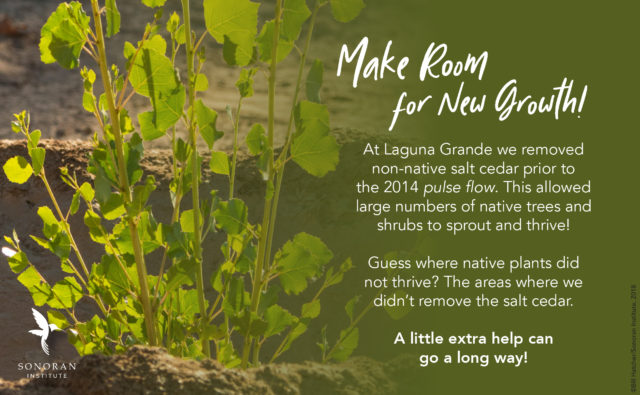

Personally, seeing thousands of little tiny cottonwood and willow tree seedlings sprout up after the 2014 pulse flow was extremely exciting and inspirational. Much of the river corridor in the Delta is covered in a non-native invasive species—salt cedar—which thrives in the highly altered conditions and reduced water flows of the Colorado River. But we found that by removing the salt cedar before the pulse flow in our Laguna Grande restoration site, we could mimic the conditions that a historic flood would bring: nice, open, moist areas of soil on which fluffy cottonwood and willow seeds carried by wind and water can land, germinate, and grow. In other areas along the river where salt cedar was not removed, the native seeds often could not get sufficient sunlight. We learned that the combination of active management and water deliveries is definitely the way to go in the future!

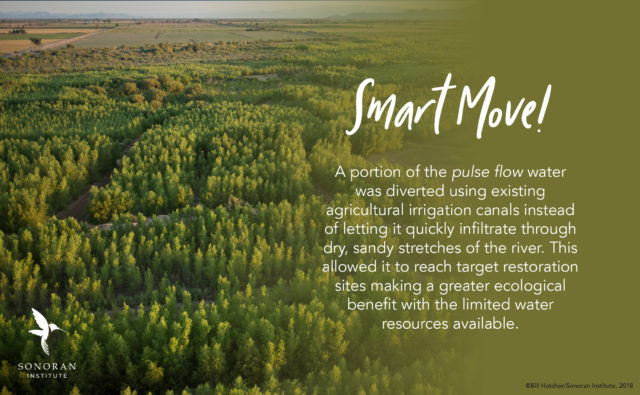

Scientists and water managers had the difficult task of trying to get the most benefit out of a very small amount of water. When thinking about how to deliver the 2014 pulse flow, we wanted to be strategic about a very dry, sandy stretch of the river in Mexico, where scientists knew much of the water would infiltrate but would have little benefit to birds and plants because of the deep water table in that area. To make the most of our available resources, we decided to route some of the pulse flow water through irrigation canals, bypassing the dry river stretch and directly delivering the water to target restoration sites further downstream. This meant that more water could be used to benefit habitat and wildlife in critical areas in the Delta.

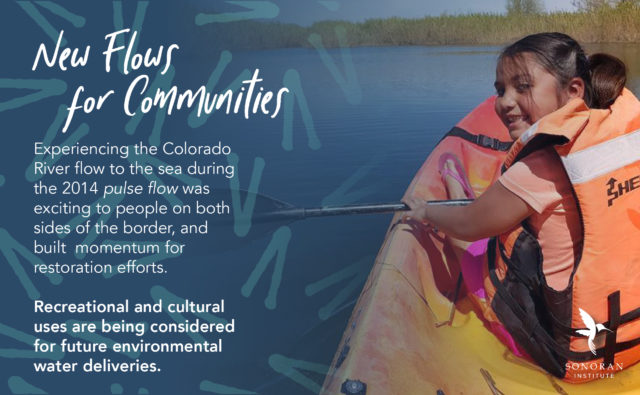

One of the most important results of the collaborative restoration and water delivery effort was the super positive response of local community members, government agencies, and people everywhere really, to the flowing river. Just imagine being a 16-year old from San Luis Rio Colorado for a second: the town was named after a river that had just been another patch of dry, sandy desert where people go to dump their trash…but suddenly became a flowing river of blue, clean water from bank to bank. (And thanks to local trash clean-up efforts in San Luis prior to the pulse flow, it was not a flowing river of trash.) Children splashed, bands played, people danced, and a global community cheered for the comeback of a delta that was given up for dead. Many scientists realized the value of water for communities, not just plants and birds. As a result, going forward under a new 9-year binational agreement that was signed in September 2017, water flows will be used to ensure that the people of the river have recreational and cultural benefits, in additional to the benefits to critters and plants.

Blog Post By: Karen Schlatter, Associate Director, Water and Ecosystem Restoration