“You feel like it’s a place that people have had deep meaningful connections to for a long time.”

—Roger Dorr, chief of resource management and park archaeologist at Tumacácori National Historic Park

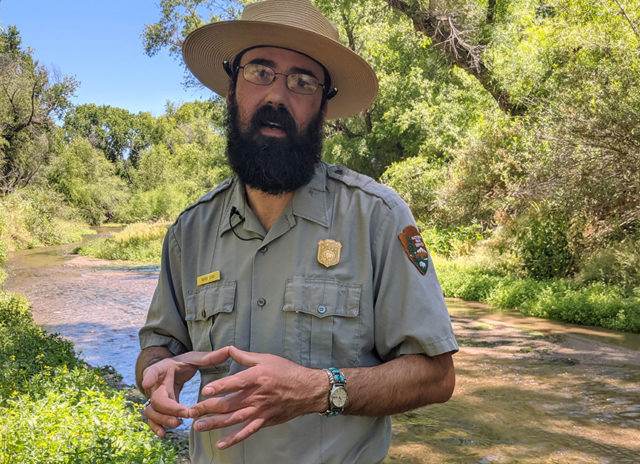

Roger Dorr is standing on a sandbar in the Santa Cruz River with little purple and yellow flowers at his feet. In the middle of the desert, this seems like a magical place. “You feel like it’s a place that people have had deep meaningful connections to for a long time,” he says. But that’s not what struck him when he first heard about the river.

Roger Dorr is standing on a sandbar in the Santa Cruz River with little purple and yellow flowers at his feet. In the middle of the desert, this seems like a magical place. “You feel like it’s a place that people have had deep meaningful connections to for a long time,” he says. But that’s not what struck him when he first heard about the river.

Roger is the chief of resource management and park archaeologist at Tumacácori National Historic Park, which protects the Tumacácori Mission and includes a one-mile stretch of the river. When he applied for the position a few years ago, he had a very different preconception of this river: “There was a discussion that the river was treated wastewater.” At first, the idea managing a river of wastewater disgusted him a little: “I was grossed out by it. In my mind, I was saying, ‘oh—yuck—okay, wastewater.’” He thought of murky, smelly stagnant pools of water.

But, he was pleasantly surprised the moment he set foot in the river corridor. As he walks along the Santa Cruz near the park now, clear water bubbles past him. A cool breeze is blowing through the tall cottonwoods, fluttering the leaves. Birds are chirping.

“In my mind it was not going to be this beautiful. Being here now, it looks pretty, clear, and fresh. I’m surrounded by a gallery forest of cottonwood and willow. It looks and feels like a magic riparian place in the desert,” says Roger. It’s true; it’s gorgeous. Walking in here you’d never know that it’s treated wastewater.

However, it was when Roger helped with Sonoran Institute’s annual Living River fish survey that he felt a real turning point: “It was a beautiful day, looking at all the fish, trying to catch them in the net, trying to see what we have. I realized, yes, it’s true, the river does depend on treated wastewater, but it makes this amazing habitat.” We’ve seen an amazing recovery in the river. After learning about the health of the river and experiencing it, Roger saw the big picture.

He points out that the river is what supported life in the region in the past as well as today: “The river helps us tell our story. This river has been a very important corridor for people in the Southwest for probably 12,000 years. There would have been hunter-gatherer and Native American villages up and down the river. That’s the reason why the missions were built along the river.”

Today, a lot of people come to the Santa Cruz to see the Mission, hike the Juan Bautista de Anza National Historic Trail, and watch the birds and wildlife. “We get tons of people who come down to this magic little spot to see rare birds from Mexico coming into the United States.”

In 2018, a park study reported that visitors to the park spent almost $2.5 million in nearby communities and supported 37 jobs in the area. Roger adds “And, that’s only the visitors to the park. Birders and horseback riders are using this area every day, and that’s not included in our numbers.”

Roger understands the water in the river is not assured, pointing out that, “The Santa Cruz River is central to our ability to tell the story of the Mission at Tumacácori. Having water in the river is critical.” The wastewater that supports the river mostly comes from Mexico, which could be diverted if resources to do so were available.

“The Santa Cruz River is central to our ability to tell the story of the Mission at Tumacácori. Having water in the river is critical.”

—Roger Dorr, Chief of Resource Management and Park Archaeologist, Tumacácori National Historic Park

“If we lost [the flowing water],” Roger explains, “we’d lose a lot of biodiversity in here. And, it’s a domino effect. That would change how cattle are run in here, it would change ecotourism. If you didn’t have the birds in this lush riparian habitat, then you wouldn’t have the birders who come down to see the birds, and they wouldn’t spend their money on the hotel room and the restaurants.”

Standing under the shade of a willow tree and surrounded by lush vegetation, Roger surrenders to the river’s charm. He’s proud to have a role in protecting this stretch of river within Tumacácori: “It’s easy to take the river for granted. We are going to need binational collaboration to safeguard the river.” We stand to lose our connection to our past and the benefits that reach far into the future.

This post is part of a a series of community voices about the Santa Cruz River.

Read the other posts by clicking the links in the introduction: When You and the River Meet

Blog series by Amanda Smith, Program Coordinator.

Copy-editing and audio-editing services donated generously by Nicole Cloutier and Jonathan Palomino.