“We need to be aware of the connection between our lives and our river. These lands, the river—they are my family’s roots. And, well, family is all we have”

—Tony Sedgwick, rancher and philanthropist

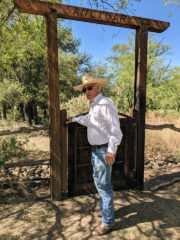

If you get the chance to visit Tony Sedgwick on his ranch in the Santa Cruz River corridor, always accept a cup of coffee and be ready for a story or two. A rancher and philanthropist, Tony heads a family that has run cattle along the border just outside of Nogales, Arizona, for three generations.

“You see those trees? I remember planting them as a kid, with my father” Tony says, pointing to the row of cottonwood trees that line the banks of the Santa Cruz River. “Back in those days, the river had water year-round. When my kids were little, they could splash around in some puddles. When I was little, I could swim! Now the river only flows when it floods,” Tony says. He recalls big floods in the 1970s and ‘80s when some of the oldest 150-foot cottonwood trees along the river were uprooted and swept away.

But, today, things are very different. This part of the river is dry, and groundwater levels in his part of the Santa Cruz River basin have dropped below the reach of his 200-foot well. “I have to choose between a shower and my swamp cooler; there is not enough water in the summer for both,” Tony says.

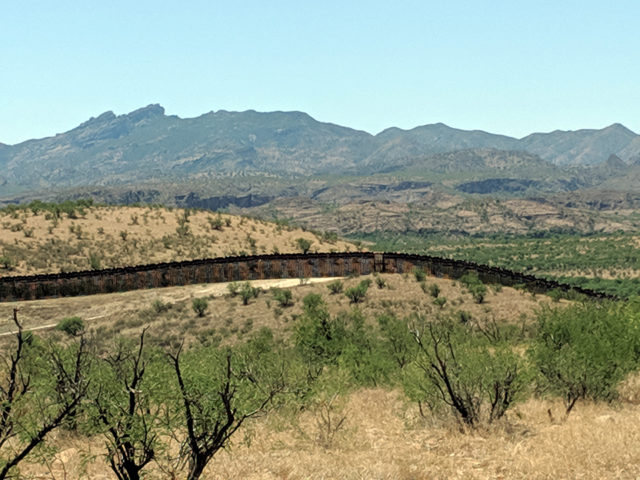

Much of the Santa Cruz River watershed is visible from Tony’s ranch, which goes right up to the U.S.-Mexico border. From atop a hill, Tony describes its course: “This river that we’re talking about, it flows south into Mexico from the Patagonia Mountains, and it flows north into the U.S. from San Lazaro and Mascarenas, up through Santa Cruz County and up to Tucson. We are one river and one aquifer, and when the rains do fall, they’re going to fall all over the place, and all that water is going to go into the Santa Cruz River aquifer. That’s what we live on.

We live from those waters.”Although a wastewater treatment plant in Rio Rico has been successfully replenishing part of the U.S portion of the Santa Cruz River for decades–thanks mainly to wastewater piped in from Sonora, Mexico–Tony’s ranch sits too far upriver to receive those restorative effects.

Instead, he’s seen the land around him transform from a river environment to a desert landscape, with mesquites taking the place of cottonwood trees as the water table drops lower. The empty riverbed offers a cautionary vision of what could someday happen to the Santa Cruz downstream as well, barring a binational solution that would assure continued water inputs from Mexico.

“No one is inventing water,” Tony laughs. “And where we are, in this river county in this desert land, we know the connection between water and life. It is not an indirect connection. You can’t teach your friends how to drink dirt. It doesn’t work. Water,” he says, “is the staff of life.”

Tony’s ranch is his forever home, his sanctuary. He does what he can to protect both the land and those who love it. Since he inherited the ranch in the 1970s, he has reduced the head of cattle and turned portions of the ranch into a place of education for the local community. The huge uprooted cottonwood tree trunks are now decomposing and useful for teaching students about the cycles of life.

Nearby, the rusty remains of Tony’s 1975 Ford pickup sit next to a mulberry tree. Tony tastes the flowers to verify the tree species. His tone softens a little, remembering all that has happened over the course of three generations on that ranch. “That sense of family is part of what the river means. We need to be aware of the connection between our lives and our river. These lands, the river—they are my family’s roots. And, well, family is all we have.”

“That and water,” Tony stresses again, returning to his energetic confidence. “Water to drink. Right there, that’s the number one priority. And as a family, as a community on this river, we need to recognize and accept our role in its survival.”

“Water to drink. Right there, that’s the number one priority. And as a family, as a community on this river, we need to recognize and accept our role in its survival.”

—Tony Sedgwick, rancher and philanthropist

This post is part of a series of community voices about the Santa Cruz River.

Read the other posts by clicking the links in the introduction: When You and the River Meet

Blog series by Amanda Smith, Program Coordinator.

Copy-editing and audio-editing services donated generously by Nicole Cloutier and Moises Munoz.