“We will be able to take what we have learned in Laguna Grande and apply it on a larger scale, throughout the entire river corridor and beyond.”

—Karen Schlatter, associate director of the Colorado River Delta at Sonoran Institute.

The only thing “grande” about what is now the Laguna Grande Restoration Area, back in 2008, was the expanse of its barren landscape and the Sonoran Institute’s belief that this part of the Colorado River Delta in Mexico could be brought back to life.

Like much of the Delta, this five-kilometer stretch of river in the Mexicali Valley was a sorry sight. Dams, diversions, and alterations for flood control had reduced the mighty Colorado to a trickle. Most of the river channels—capillaries that branched off from the main artery—were clogged by a build-up of sediment that the weak flow of water, if there was one, was unable to breach. Disconnected and dried up, these historic channels were unable to deliver life-sustaining water and nutrients to the surrounding land.

The area was overrun with tamarisk (salt cedar), an invasive shrub that choked out the native cottonwoods and willows that historically provided critical habitat for migrating birds and other wildlife. The fact that there were small numbers of native plants growing showed that the site had potential for restoration. However, the days of plentiful beavers, lynxes, foxes, raccoons, coyotes and big cats, like bobcats and pumas were gone. Gone were the gigantic flocks of green- and blue-winged teals that had nearly obscured the skies. The Delta’s human community was under considerable stress as well. Lacking water and game, the fishing and hunting industries that once provided jobs and sustenance had withered.

Amid so much degradation, the Sonoran Institute saw hope. “We had seen from the new growth after flooding events in the late-90s how resilient the Delta actually is,” says Francisco Zamora Arroyo, director of Sonoran Institute’s Colorado River Delta Program. “Given a small flow of water, we believed we could bring this part of the Delta back to life.” With longtime conservation partner Pronatura Noroeste, the Sonoran Institute set about realizing Francisco’s vision. In 2008, the partners secured 1,200 acres through a land concession agreement with the Mexican government and embarked on a mission to create a thriving nature preserve.

Almost a decade later, Sonoran Institute has planted more than 200,000 trees and restored 700 acres, helping make Laguna Grande the largest and most dense stand of native riparian habitat along the Colorado River in Mexico. Building on these achievements, a new binational water-sharing agreement signed in September 2017 includes a plan that doubles restoration goals for the area. Laguna Grande is truly beginning to live up to its name.

A Living Laboratory

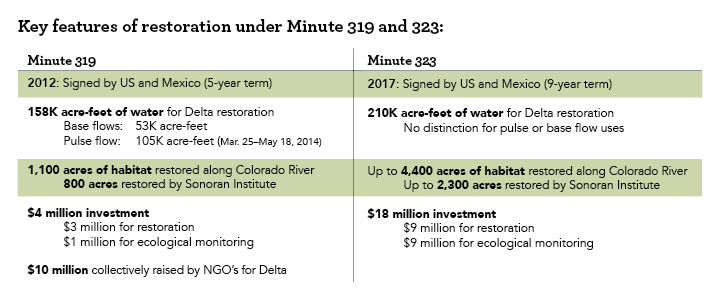

Over the years, Laguna Grande has served as a “laboratory” for Sonoran Institute to test and develop the most effective methods for reviving the Colorado River Delta’s riparian corridor and estuary. This research was instrumental in laying the foundation for Minute 319, a 2012 amendment to the U.S.—Mexico Water Treaty of 1944. Prior to this amendment, 100 percent of the Colorado River water flowing into Mexico was diverted into irrigation canals at the Morelos Dam, near the U.S. – Mexico border. In other words, none of the water continued its flow directly through the river channel into Mexico until Minute 319 expanded Delta restoration efforts and, for the first time in history, dedicated water to the river for environmental purposes. This water dedication included a small but constant “base flow” provided to maintain habitat and groundwater levels at restoration sites along the riparian corridor, and the floodgate-opening historic “pulse flow” of 2014.

“The pulse flow was a monumental experiment,” says Karen Schlatter, associate director of the Sonoran Institute’s Colorado River Delta team. “It was a provision in Minute 319 designed to mimic the spring flooding that would naturally occur if not for the dams and other human alterations to the Colorado River. Nothing like it had ever been tried before in the Delta.”

Beginning in March 2014, 105,000 acre-feet of water[1] was released into the river from Morelos Dam over a two-month period. Water coursed down the entire length of Mexico’s stretch of the Colorado River until, in mid-May, it reconnected to the sea for the first time in sixteen years.

Scientific Approach Increases Biodiversity in Restoration Sites

Thanks to Minute 319’s base flows, visitors to the Laguna Grande restoration area immediately see a wall of green—a forest of tall trees—and a river with water. Water is the key ingredient for restoration success, but adding water alone would not have yielded the diversity and proliferation of native habitat that Sonoran Institute has achieved. The restoration work is carefully designed to ensure every drop of available water has an impact, and it has created the most wild, forested area in the Delta.

“Many of the achievements in Laguna Grande have to do with our techniques, the methods we are using,” says Schlatter. “Our scientific approach to restoration within the Delta is unique.” Initially, she explains, Sonoran Institute modeled its efforts on riparian restoration work that used an agricultural approach, digging furrows and planting target riparian tree species. The resulting trees grow up in neat rows, all the same height.

“It’s a tree farm, essentially,” Schlatter says. “We’re moving away from this approach, experimenting instead with techniques that would bring more diversity and would be closer to what existed along the riparian area in the Delta 100 years ago.”

To this end, the Sonoran Institute hired a botanist to inventory the plants present in the restoration sites and analyze the historic species. The results of this study form the list of species the Delta team is working to reestablish in Laguna Grande. While many species are grown from seedlings or saplings in the Sonoran Institute’s tree nurseries and planted by hand, the organization has also experimented with direct seeding with native tree seed, which increases genetic diversity and habitat resilience.

Developing different irrigation techniques has also yielded greater diversity of plant species and habitat types. As an alternative to flooding restoration sites, the Delta team delivers water to restoration sites via river meanders and lagoons that raise groundwater levels in the area and support a variety of vegetation. “As a result,” Schlatter says, “we have really interesting sites now that have marsh and lagoons with intermittent stream areas and cottonwood-willow gallery forest. Other sites are planted with diverse native shrubs and flowering herbaceous species to target pollinator insect species. It’s pretty cool.”

The model of experimenting on a small scale and applying lessons learned to larger projects paid dividends during the pulse flow of 2014, when the Delta team put creative restoration techniques into practice. Sonoran Institute saw an opportunity to use the river’s own natural water delivery system—the dried-up historic river channels—to greatly expand the pulse flow’s impact. The team prepared for the pulse release by bringing in machinery to dig out and grade the sediment obstructing the channels, and by clearing away the tamarisk and other non-native vegetation that overran the channels and surrounding floodplain.

“We had the foresight to reconnect some of the historic channels to the Colorado River mainstem at Laguna Grande to get the most benefit out of the flow,” Schlatter says. “When the pulse flow came, these off-channel areas flooded as well. And, since the nonnative plants were removed, it was ready for native seeds to land and germinate. These active management steps allowed for additional acreage and new habitat establishment that otherwise would not have occurred.”

Flocking Back

The Delta is a key stopover point on the Pacific Flyway, the migratory bird route from South America to Canada. Loss of habitat along the route over the last century has severely reduced the migratory bird numbers, but Laguna Grande is already proving to be a haven for both migratory and nesting bird species. “The restoration efforts have had a great impact on birds,” says Osvel Hinojosa, director of the Water and Wetlands Program at Pronatura Noroeste. “They are flocking to the restoration sites because they have good habitat and water.”

An interim report on the effects of Minute 319 compiled for the International Boundary and Water Commission in 2016 found that bird diversity and abundance had increased throughout the Colorado River corridor after the pulse flow, and was significantly greater in the Laguna Grande restoration sites than anywhere else along the river. In fact, the report found that the numbers of bird species targeted for conservation were 43 percent higher in the restoration areas than in the rest of the floodplain between 2013—2015. These species include hooded oriole, yellow-breasted chat, vermillion flycatcher, Gila woodpecker, and cactus wren. The endangered yellow-billed cuckoo is also using Laguna Grande as a stopover point.

“Particularly when you consider that the Pacific Flyway includes such arid stretches through Mexico and into the southwestern U.S., having these restored areas and wetlands available for stopover points is really critical for these species to rest, recover, and get water,” Hinojosa says.

Birds are not the only creatures migrating back to Laguna Grande. Coyotes, bobcats, and beavers are among other the species reappearing. Eventually, as Sonoran Institute works to create a flowing river from Laguna Grande to the river estuary the team hopes to see a return of native fish species to the river.

Reviving a Community

Along with restored habitat and water in the river come increased economic opportunities for Delta communities. On the nearby Hardy River, a tributary of the Colorado River, the tourism and hunting industries are growing along with better water flows and improved conditions for doves, pheasants, ducks, and geese. In Laguna Grande, the return of the birds has awakened interest in birdwatching and ecotourism. Community members near the restoration sites formed Alas del Delta (“Wings of the Delta”), a birdwatching group that also operates as a guided birding tour business.

“It’s really exciting to see the improved habitat generating jobs for the local community,” says Schlatter. She notes that Delta restoration work itself has become an important source of employment. At the Delta program’s field office in Mexicali, Sonoran Institute is drawing talented people from all over Mexico. “People are really excited to become part of our team and work with us long term,” she says.

Out in the field, the Sonoran Institute annually employs 25-40 staff positions in the Delta. “Between the Sonoran Institute and our partners doing restoration work, our overall impact on jobs in the area is significant,” Schlatter says. In an area where full-time jobs are hard to find, the options for many of the people now doing fieldwork for Sonoran Institute were limited to working in agricultural day-labor jobs, with low pay, little prospect for advancement, and seasonal layoffs.

Sonoran Institute has been able to provide both good jobs and valuable opportunities. “Our employees have diverse life stories, but typically start with little restoration experience or education.” Schlatter says. “Through our training and after years of working with us, they are now experts in restoration and ecological monitoring. They know bird species, recognize bird calls, and are excellent botanists. Many are women, and many are now in leadership roles on the restoration team.” Perhaps no one better exemplifies how empowering this work can be than Celia Alvarado Camacho, a local woman who began as a temporary employee and has risen to become a restoration field supervisor.

Over the years, Sonoran Institute has engaged community members in experiencing the Delta’s revitalization in other ways as well, bringing thousands of local school children to Laguna Grande for environmental education programs, and attracting volunteers of all ages to plant trees and help with other on-site restoration work. The long-term success of restoration efforts and the Delta itself will depend on these communities.

A Grand Vision, Within Reach

The success of Laguna Grande and the other restoration efforts under Minute 319 have led to even more ambitious goals for the Delta. Additionally, Minute 323 ensures improved water security for Colorado River water users across the basin and expands the scope of restoration efforts.

In collaboration with Raise the River (a coalition of U.S. and Mexico environmental groups dedicated to restoring the Delta), Sonoran Institute expects to double the restored area to 1,300 acres of habitat in the next five years. These sites will extend beyond the Colorado River corridor to include the river’s tributaries and support the innovative restoration work Sonoran Institute is leading in the Delta’s estuary and surrounding wetlands.

“With this new agreement, we will be able to take what we have learned in Laguna Grande and apply it on a larger scale, throughout the entire river corridor and beyond,” Schlatter says. “It has been amazing to be part of the Delta program’s achievements and the binational agreements. Led by Francisco, the Sonoran Institute’s vision for the Delta made all of this possible.”

[1] An acre foot is the amount of water it would take to cover an acre of land at a depth of one foot.

Read Celia’s inspirational story!